- November 9, 2021

- ERNL

Culture challenge

Recently I came across this article I wrote on LinkedIn back in 2015 already, and Gosh, it throw me how actual I believe its content still is.

Culture I believe will remain a constant challenge for the organisations, culture risk is one of the latest business topics we discuss in board rooms. The last 20 months brought a total new challenge to organisational culture: “How will organisations ensure the right culture is deployed consistently in a hybrid working environment?”.

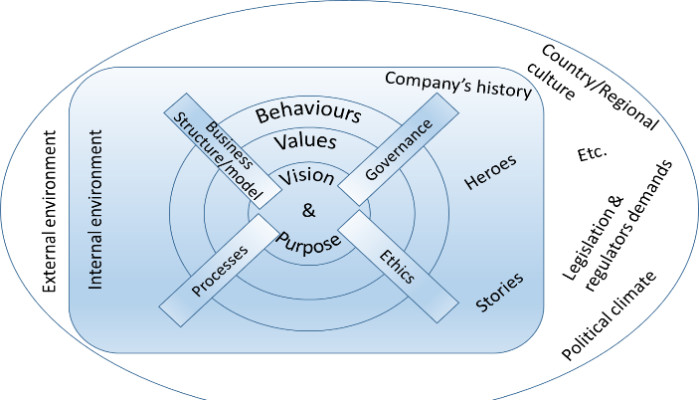

I suppose the pandemic and its wide impact on organisations is a life example of the external environment’s risks on culture, as illustrated in my culture factors diagram (own source included in master thesis).

Original article: “Don’t ignore the culture challenge”, LinkedIn, June 2015, E.R. Nistor-Lustermans

Over the last decades organisations struggled to establish an effective relationship between their operational processes, the human factor and its impact on organisations output. Bankruptcies as well as success corporate cases were ultimately all linked to a human factor, which corporations tried to ignore by implementing tight processes and controls.

All most half century ago, Milton Friedman was quoted for the following about business purpose: “there is one and only one social responsibility of business, to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition without deception or fraud” (Milton Friedman, 1970). In the last decade we see more and more focus on organisations social responsibilities, values and behaviours, after decades when greed seems to have ruled the board rooms.

Cases as Enron, Parmalat and others showed that corporations under strong pressure for profit and fame did not always engage in open and fair competition. Wrong corporate governance, lack of appropriate internal control and tone at the top where some of the issues which led to the failure of those corporations. To fix some of these issues changes were made to guidelines regarding corporate governance. Sarbanes Oxley Act (2002) was one of the regulations introduced in the hope to reduce the probability of similar failure scenarios to be repeated. However the solutions which at that time were thought to fix the issues, did not work for all companies and could not fix all business issues around fraud, tone at the top and personal greed, as years later, in 2008, a new storm of bankruptcies happened.

The financial crisis in 2008 and the collapse of some financial institutions have partially been associated with the wrong internal culture; which made the business world question even more what good corporate governance is and how to apply ethics in business. The stakeholders are demanding more assurance on corporations’ decision making process, on the organisational culture and the business ethics.

I remember the annual conference of the UK Institute of Internal Auditors in 2013, where auditing culture was one of the topics most discussed. There were more questions around the subject than practical guidelines: can organisational culture be audited? what is actually organisational culture?; how can we audit it?; which are the skills the auditors need?; how can overall assurance be given that an organisation has the right culture?

The new UK Corporate Governance code, updated in September 2014 emphasises the role of the boards related to culture, values and behaviours: “One of the key roles for the board includes establishing the culture, values and ethics of the company. It is important that the board sets the correct ‘tone from the top’. The directors should lead by example and ensure that good standards of behaviour permeate throughout all levels of the organisation. This will help prevent misconduct, unethical practices and support the delivery of long-term success” (FRC, 2014).

IIA issued in the last years a number of guidelines on auditing culture, E.G. Best practices: evaluating the corporate culture by James Roth (2010); Culture and the role of Internal Audit by Philippa Foster Back (2014); and Auditing culture by CIIA body (2014); and most of the big organisations in the City started getting interested in the topic.

Internal Audit (IA) is seen as the right function within the organisation to provide such an assurance. Its appropriateness comes from the fact that IA does not have direct managerial and operational responsibilities for the everyday business and its historical role is to provide independent assurance that an organisation’s risk management, governance and internal control processes are operating effectively. Traditional auditing focuses on assessing hard facts like defined processes and procedures, where the organisational culture deals with the soft side of an organisation; which is not always captures in processes and procedures; making auditing culture a new challenge for auditors.

Recently, I wrote an academic paper on how organisational culture can be audited, and for its purpose I reviewed the IIA guidelines on auditing culture and I did a case study on the IA (of one of the Big UK banks) approach to auditing culture. This research was an open eye to how complex the culture topic is and how big the challenges posed by the culture aspects are for an organisation.

If I have to give a short answer to “Can organisational culture be audited” I would say no, organisational culture as such can’t be audited. There is no “fits all” audit programme on auditing culture which can be taken for the shelf and used as such. Organisational culture, defined mainly as “the way we do things around here” (A.Kennedy, 1982) or “programming of the mind” (Hofstede, 2010), is a very complex aspect of a corporation’s life. To define its culture an organisation needs to defined its values, believes, behaviours, stories of good actions, its structure, distribution of power and its decision making approach which needs to be in line with the organisation’s vision and purpose. Values can’t be assessed, but the behaviours and the actions driven by those values and their impact on processes and internal controls can be evaluated.

Organisation’s culture aspects are very complex they are influenced by the soft and hard controls. There are many organisational culture models which can be used to understand what type of culture an organisation has, and there is no best or worst model to use, it just depends on an organisation vision and purpose.

I believe Internal Audit has a duty of understanding an organisation culture, its impact on the internal control and how the board approaches the culture challenge.

As the business environment changes faster than ever before, and organisations are going through constant changes; the culture aspect is heavily challenged by the transition phases, by international and regional cultural influences. The old way of doing things is put under the pressure of the transformation, and people’s behaviours will be impacted by the changes in processes, the change of values, attitudes and stories. During a major business and organisational transformation employees will most probably change their attitude to processes and internal controls and they will be more sensitive to the company’s heroes and stories.

Internal Audit, as a function, has to be tuned to capture as much as possible these soft aspects of an organisation and to go that one step further in analysing the audit findings, by questioning if the culture’s aspects (tone at the top, values, behaviours, people’s attitudes to control) are the root cause of the issues. This requires the auditors to have very good analytical and listening skills, to be open minded, and to apply an increased dose of professional judgement to capture all aspects of the culture’s challenge and to engage with confidence in assessing behaviours and the unwritten stories’ impact on internal processes. Furthermore auditors need to be aware of their own culture and the impact their own believes have on assessing the wider organisation culture and get courageous in stating opinions which are not based on hard evidence.

It was once told to me that auditing culture is a journey, and I do believe this is true. An organisation culture evolves and changes continuously because it is influenced by all kind of internal and external factor, through which also an important influence comes from the human factor. Therefore evaluating culture does not stop once a framework or approach has been developed and used, but it needs to evolve and be adjusted to ensure it continues to be relevant for the organisation. The auditors need to see their work as an on-going assessment of the culture’s impact on internal control and governance.

It comes clearer than ever that employees behaviours, values and believes are ultimately impacting an organisation’s’ governance. For those companies who are going through transitions and transformations phases understanding the gap between a desired culture and the exiting culture can be essential to success. Culture remains a complex and challenging subject which the boards struggle to tackle in a concrete way and which needs the full attention of the leadership team to ensure its associated risks are fully understood. Today boards are getting increased pressure from regulators to pay more attention to all organisation’s soft controls and their impact on the business. IA challenge is to present the findings linked to organisation’s soft controls in a tangible way, so that they can be understood and actioned. I think the assessment of soft controls shall be embedded in all audits, as part of identifying the root cause of the internal control and process failures. The main driver for assessing a company’s culture shall be the board’s requirement to get assurance that the company has the right believes and behaviours to supports the delivery of its purpose and vision. (By E. R. Nistor-Lustermans, 2014 MSc Dissertation)

Setting vision and goals for 2023!

As we all dive into 2023, for some of us the beginning of the year is an exciting time to set new goals or review…

“80% of success is showing up”

Celebrating the first year of showing up in my business! 2022 was my first year of business for ERNL. Officially my company exists for soon…

Celebrate the small steps, they are part of your bigger journey!

Right in time for the upcoming festive season, my latest article in HOWDO magazine article is a reminder of the importance of celebrating small successes! Online…